One-of-a-kind VCU and VA program prints 3D replicas of patient’s body parts

Through nation's first 3D printing surgical fellowship, VCU researchers are using anatomy replicas to improve the surgery experience for physicians and patients.

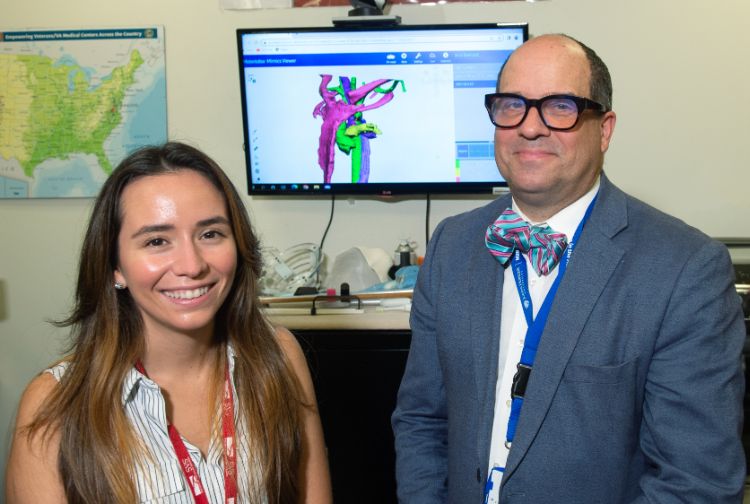

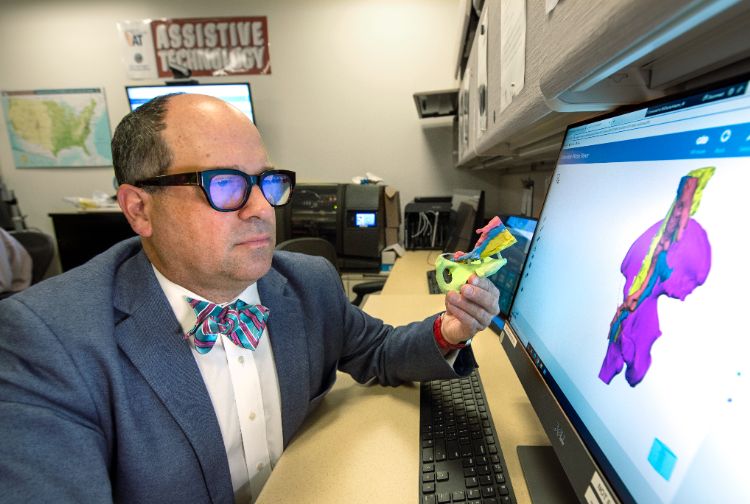

November 11, 2022 Michael Amendola, M.D., reviews a 3D print created as part of a surgical fellowship program he oversees with the VCU School of Medicine at the Central Virginia VA Health Care System in Richmond.(Kevin Morley, University Marketing)

Michael Amendola, M.D., reviews a 3D print created as part of a surgical fellowship program he oversees with the VCU School of Medicine at the Central Virginia VA Health Care System in Richmond.(Kevin Morley, University Marketing)

The surgeon orders a scan, uploads it to her computer and hits print. At the end of the hall, a 3D printer creates what she needs – a replica of the patient’s organ with a difficult tumor embedded within it.

That’s the future Michael Amendola, M.D., and Diana Otoya, M.D., know is coming. And through a new surgical fellowship with the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine at the Central Virginia VA Health Care System (CVHCS) in Richmond, they're preparing surgeons for that future. The 12-month fellowship, funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense, is the only one of its kind in the nation.

“We work in a three-dimensional world. We operate in it. We solve problems in it,” Amendola said. “The anatomy should be presented, ideally, in 3D.”

A 3D printed model of a skull in a complicated surgical case, showing the intracranial pathology. (Central Virginia VA Health Care System)

Amendola, chief of vascular surgery at CVHCS and professor in the VCU School of Medicine’s Department of Surgery, was drafted into the 3D printing world in 2021. While he and Beth Ripley, M.D., the head of 3D printing for the nationwide VA system, only had a 20-minute meeting on the books, Amendola says it became a four-hour conversation about how he could help expand 3D printing technology across the VA – at the hospital level.

Amendola has since led the charge for pre-surgical modeling at the CVHCS, helping make it a leading site for medical 3D printing nationally.

“We're at the very beginning of this – which is why teaching and studying it is so important at this stage,” he said.

3D printing is also used for other fields at the VA, such as printing a wheelchair joystick to exactly match a patient’s hand mobility. Another long-term project aims to “bioprint” replacement organs for patients as they’re being operated on.

“The vision is for every single veteran to be able to have access to this technology,” Otoya said. “Right now, we're able to ship models from the VA across the country. Eventually, one day, there’ll be 3D printers in every single VA.”

There are 3D printing fellowships in radiology, but this is the first in surgery. Otoya is part of the first group of fellows for the program and has enjoyed it so much that she’s staying on for another year to help develop additional coursework and advance the field. The other two fellows, Sally Boyd, M.D., and Lucas Keller-Biehl, M.D., are continuing their research residency at VCU Health.

A big part of the training is educating others as well as teaching fellow doctors what is possible – and not possible – with 3D printing.

“The value of these models – being able to show something, hold something, physically manipulate it – is incredibly valuable,” Otoya said. “It gave me a new perspective on how to problem solve and how to think of anatomy. Now when I look at a CT scan, my brain is slowly reprogramming it to view it in 3D.”

Diana Otoya, M.D., and Michael Amendola, M.D. (Kevin Morley, University Marketing)

For surgeons, this means being better prepared to enter the operating room. A 3D-printed model of a tumor’s precise location in the brain can show them how to remove the least amount of brain tissue during a surgery. In another case, a 3D-printed kidney helped surgeons decide against an operation and pursue different treatment.

For patients, 3D printing makes it easier to decide what kind of care they want to receive.

“The patient with a kidney tumor said, ‘It all sounds like gobbledygook to me, but when you print it and put it in my hand, there’s incredible power to understand,’” Amendola said.

Surgeons can effectively communicate what they want to do or not do. For example, one patient with a cyst on a vein ultimately decided that she didn’t want to have the surgery, after holding the model.

Amendola adds that printing at the hospital level is the future. All providers and especially all surgeons, Amendola hopes, will one day be familiar with 3D printing and its capabilities.

“We are at the beginning of a personalized medicine revolution,” Amendola said. “3D printing is a tool in that revolution, and surgeons are going to use it more and more.”